An experimental art method.

Drawn largely from postmodern critiques, experimental art methods allow artists to discover and investigate problems, expose limits of art practices and analyze art making processes. Francis Alÿs2005 artwork Sometimes Doing Something Poetic Can Become Political, and Sometimes Doing Something Political Can Become Poetic utilizes the situationist artistic method called ‘derive.’ ‘Derive,’ denoted as involving desultory travel through various ambiances, was revolutionarily asserted by French theorist and film-maker Guy Debord in his 1956 paper ‘The Theory of Derive.’ He described the method as a means of exploration and awareness of the effects of geographical locations on the behaviour and emotions of individuals (Deboard, 1956). Utilizing this technique, the artwork features Alys tracking the armistice boundary that was marked with green pencil at the end of Israel’s War of Independence in 1948 with a can of dripping green paint (Ruben Aberjil, 2007). Considering the ‘speed culture’ of the present day, in direct correlation Aly’s explained the utilization of the technique as a form of resistance that is both the means of art production and a method for ‘artistic transaction’ (Russell Ferguson, 2008). His artwork both employs and critiques the method, exploring the axiom of its title by questioning whether an intervention so presumably meaningless can provoke social change and reflection and if it can be done with the absence of applied doctrine or activism. Described by art critic Holland Cotter as “connecting art to the larger world” (Cotter, 2007) the method itself has marked a revolutionary point in art-making in which the production of the artwork is left to the possibilities of psychogeorgraphical variations and the meanings one can derive.

FRANCIS ALYS Sometimes Doing Something Poetic Can Become Political, and Sometimes Doing Something Political Can Become Poetic, 2004.

How the post modernism notion of difference changes the idea of knowledge.

ANDY WARHOL Self Portrait, 1967.

As a direct response to the concept of ‘structuralism’ in modernism, postmodernism explores the notion of difference and how it challenges traditional ideas of knowledge. Andy Warhol’s 1967 Self Portrait is reflective of a perception of self which is non-binary and open to elusive change, rejecting notions of fixed meaning. Warhol as a key post-modernist artist embodied the paradoxical suspension between the isolation of high art and the repetition of capitalism; this characterised postmodernism as movement emerging parallel to consumer culture and expressed the deeper logic of that social system, according to American literary critic and philosopher Fredrick Jameson. Jameson outlined that post-modernism essentially rejected the notion of progressive history, instead residing in a perpetual, ever-changing present that obliterates tradition (Jameson, 1983). While Self Portrait utilizes repetition, the diversity and uniqueness of the colour combinations of each panel as well as the absence of distinctive form reflected Warhol’s rejection of cultural and societal tendencies to decipher fixed meaning and universal knowledge. As with all Warhol’s work, hand gesture is completely removed from the artwork, expressed by Warhol himself as an intentional way of being anonymous and noncommittal (Tate, 2019). His desire to remain elusive was recognized by critic D Bourdon who stated his “self-portraits offered no detailed information about either his physiognomy or his psychological state; instead, they present him as a detached, shadowy, and elusive voyeur” (Bourdon, 1995). In this sense, his artwork is a tangible expression of a rejection of traditional views of knowledge in how it demonstrates the commitment of post-modernism to explore difference.

How artists have critiqued the medium of the white cube gallery.

For the Lecture: The social organism – a work of art (1974) is a lecture delivered by German artist Joseph Beuys on ‘humanity’s natural creative capacity and the power of direct democracy to shape society’ (Gregory, 2019). The artwork critiques the medium of the white cube gallery by making the act of teaching the artwork, challenging the notion that art had to be a tangible object restricted to the confines of an institution. Key media theorist Marshall McLuhan, famous for his assertion ‘the medium is the message,’ argued in the late 1960s that anything can be validated as art as long as it exists within the institution of the gallery (McLuhan, 2001). A major aspect of the post-modernist art movement sought to question and critique these boundaries. According to the writings of artist and theorist Sol LeWitt, the conceptual aspect of an artwork is superior and should transcend the medium (LeWitt, 1967). In accordance with this, Beuys dismissed the tangibility of objects in an interview with Artforum in 1969, expressing the ‘origin of the matter... The thought behind it’ as moresignificant, stating therefore that “teaching is my greatest work of art” (Abrams, 2016). His ‘performance lecture’ is a form of anti-gallery ‘process’ art where the process of learning itself creates the work. In opposition to Marshall’s reliance on the gallery space, the ‘performance lecture’ produces an artwork consisting solely of ideas requiring an audience but can still exist outside the gallery space. For the Lecture: The social organism – a work of art is a direct embodiment of the key principles of post-modernism that sought to critique the medium of the white cube gallery in its validation of conceptual, process art.

How gender is represented and how this representation complicates the notion of binary gender as natural or normal.

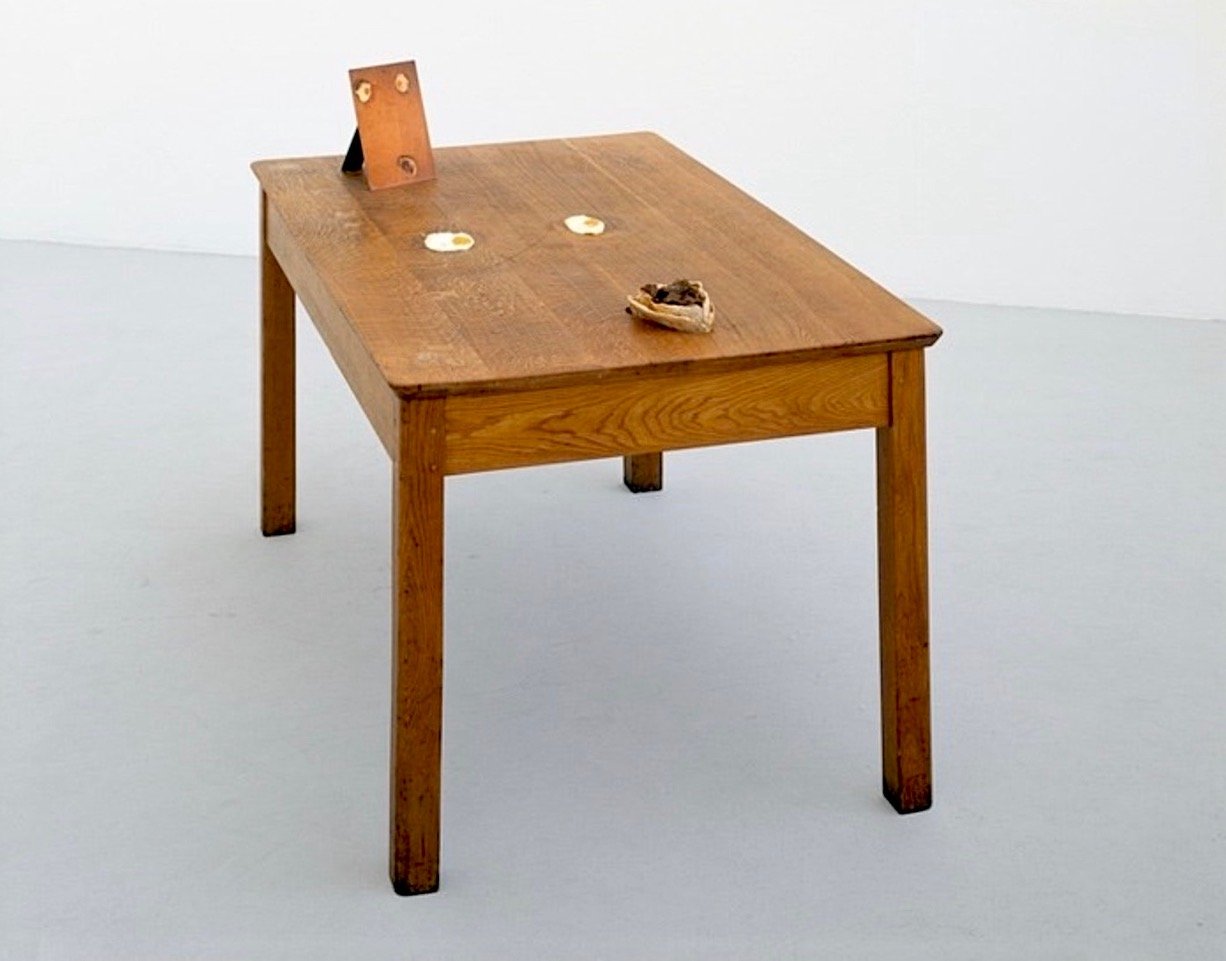

Two Fried Eggs and a Kebab (1992) by English artist Sarah Lucas explores the repetitive performance of gender, eluding to its depth and complicating the notion of gender as a binary spectacle. The artwork consists of two fried eggs and a kebab arranged on a table each day in a crude materialization of the misogynistic comparisons heard by Lucas between that and her breasts and genitalia (Nelson, 2018). Associating the female body with food removes its sensuality, challenging traditional erotic representations of women enabled by the male gaze. The absurd surrealism of the artwork ensures the exploration of gender and sexuality is the focus, but not an erotic spectacle (Mulvey, 1989). This representation of white heterosexual femininity alludes to what writer and curator Beatriz Preciado refers to as the sexualized economy of gender fostered by ‘performative coercion’ that generally alludes to the exclusive existence of binary genders (Preciado, 2013). Freshly laying the imagery on the table daily references Judith Butler’s claims in her thesis, ‘Gender Trouble,’ that the perception of gender as naturally binary is a consequence of repeated performances encouraged inherently by societal ‘norms.’ Consequently, the oil residue that stains the table by the end of the exhibition reflects these normalized behaviors as expected and integrally inscribed (Gregory, 2019). An artwork with multi-faceted meaning, Two Fried Eggs and a Kebab critiques the sexualization of women while challenging the notion of binary gender as ‘natural’ in its representation of gender as a performative construct.

SARAH LUCAS Two Fried Eggs and a Kebab, 1992.

How artists have critiqued and challenged colonial rule and the idea of Australia as a white possession.

TRACEY MOFFATT Heaven, 1997.

Since the 18th century, artists have constructed representations of the dispossession of Australia by British Colonists. As an artwork that inverts the perception of colonial rule, Heaven (1997) by Aboriginal/Irish artist Tracey Moffatt exposes the inherent entitlement of white masculinity to the beach, a supposed symbol of collective pride and nationalism in Australian culture. The 28-minute long short film is a collection of footage of male surfers publicly changing in and out of wetsuits around the iconic beaches of Sydney shot in a shaky home-video documentary style. While the film has been interpreted as an exploration by Moffatt into the female gaze, according to cinema writer Raffaele Caputo, she is an artist who primarily considers the history and context of place (Caputo, 1993). The key setting of the artwork, the beach as a place of pleasure, leisure and pride is a symbol of collective national ownership and the Australian identity. While historically the beach was a location of violence and dispossession for Indigenous people by colonized nations, according to academic and activist Aileen Moreton-Robinson, the oppression of Indigenous Australians has become nullified through the cultural normalization and sanctification of white male bodies on the beach (Moreton-Robinson, 2018). In correlation with this, as the glorified surfers parade through Moffatts clips, the soundtrack comprising of chants of Aboriginal Australians grows louder, marking the absence of Aboriginal beach culture and questioning whose heaven is being portrayed (Bergo, 2016). As a symbol of both division and unity within Australian culture, the utilization of the beach in Moffatts artwork combined with the glorification of male surfers critiques Australia’s national identity and the idea of the white possession of Australia.

Abrams, A.-R. (2016, January 19). The Weird and Wonderful World of Joseph Beuys. Retrieved from artnet: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/joseph-beuys-408125

Bergo, C. (2016). The Affective Landscape: Place, Trauma and Hauntings in the Works of Tracey Moffatt. Retrieved from Academia: https://www.academia.edu/26432070/The_Affective_Landscape_Place_Trauma_and_Hauntings_in _the_Works_of_Tracey_Moffatt

Bourdon, D. (1995). Warhol. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

Caputo, R. (1993). BeDevil: Tracey Moffatt. Cinema Papers.

Cotter, H. (2007, March 13). Thoughtful Wanderings of a Man With a Can. Retrieved from The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/13/arts/design/13chan.html

Debord, G. (1956). Theory of the Dérive. Les Lèvres Nues #9.

Gregory, T. (2019, October 21). DART1301 Post Gender, week 6, term 3 notes [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from https://echo360.org.au/lesson/G_af241536-e955-4d12-81fe- b8b3538d8b46_b409b1ff-c4e7-40c1-b3f4-57f5445ce886_2019-10-21T10:05:00.000_2019-10- 21T11:25:00.000/classroom#sortDirection=desc

Gregory, T. (2019, October 14). DART1301 Post Medium, week 5, term 3 notes [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from https://echo360.org.au/lesson/G_af241536-e955-4d12-81fe- b8b3538d8b46_b409b1ff-c4e7-40c1-b3f4-57f5445ce886_2019-10-14T10:05:00.000_2019-10- 14T11:25:00.000/classroom#sortDirection=desc

Jameson, F. (1983). Postmodernism and Consumer Society. In H. Foster, Postmodern Culture (p. 125). London: Pluto Press.

LeWitt, S. (1967). Paragraphs on conceptual art. Artforum, 79-83.

McLuhan, M. (2001). The Medium is the Massage. USA: Ginko Press. Moreton-Robinson, A. (2018). Bodies That Matter on the Beach. e-flux.

Mulvey, L. (1989). Visual and other pleasures. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Nelson, M. (2018). Sarah Lucas. London: Phaidon.

Preciado, B. (2013). Testo junkie : sex, drugs, and biopolitics in the pharmacopornographic era. New York: The Feminist Press at the City University of New York.

Ruben Aberjil, A. A. (2007). Francis Alÿs: Sometimes doing something poetic can become political and sometimes doing something political can become poetic. New York: David Zwirner.

Russell Ferguson, J. F. (2008). Francis Alÿs. London & New York: Phaidon.

Tate. (2019). Andy Warhol Self-Portrait. Retrieved from tate.org.uk: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/warhol-self-portrait-t01288